Exclusive Interview

Dec 11, 2024

Produced by: Andrej Aroch

Edited by: Rudy Manager & Andrej Aroch

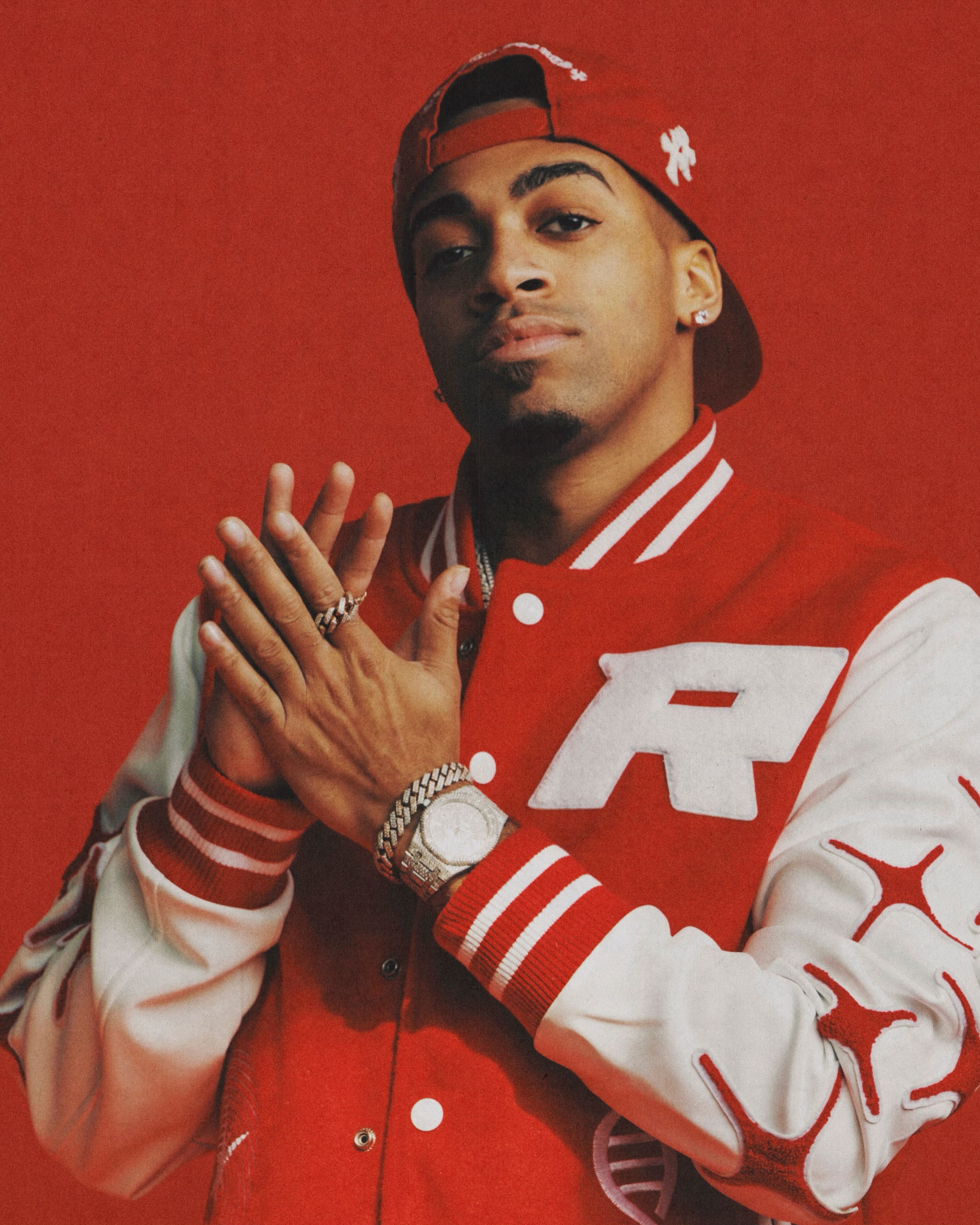

Al Hug – Zurich Producer Behind J. Cole, Headie One & Chance the Rapper

In this exclusive interview with Al Hug, a talented music producer based in Zurich, Switzerland, we dive into his journey in the music industry, his unique approach to sample production, and the creative process behind some of his standout tracks. Al Hug has worked with top-tier artists and carved out a distinct identity with his innovative sampling techniques. Throughout the conversation Al Hug shares valuable advice for up-and-coming producers, emphasizing the importance of finding your own path and staying true to what excites you. This interview was conducted by Andrej Aroch via a video call on November 27th, 2024.

“Everything you need to know about music is already in the music itself”

- Al Hug

How did you get interested in music? And from that, how did you transition into music production?

Music was always a big part of my life—it ran in the family on both sides, my mom’s and my dad’s. It was always really important. So when I was about six years old and said, “I want to play drums,” the response was immediate: “Yeah, you can do this. If you want to play drums, you can play drums.” From that point, I just kept playing instruments. Around age 12, I also picked up piano.

We lived in a very remote area, with almost no neighbors, so I often had to find ways to entertain myself. Making music became one of the main things I did to stay engaged and avoid getting bored.

Music production came into the picture a bit later, maybe when I was around 15 or 16. My best friend’s brother had started making beats, and my friend began rapping. But for some reason, either his brother didn’t want him to use his beats, or maybe his brother just said, “No, you can’t rap on my beats.” So he turned to me and said, “You make music—why don’t you make beats for me?” That’s basically how I started making beats.

After high school, I decided to study music and went to music school. During that time, I put music production on hold and focused solely on practicing instruments and playing live. It wasn’t until after I finished music school—about eight years ago—that music production became important to me again.

You mentioned you first picked up music production around the age of 16. What was your process of improving back then? Was it trial and error, or did you rely on something like “YouTube University,” so to speak?

For me, it was really about learning from the people around me. From the very beginning—and this is still true today—I have learned by listening to music. Everything you need to know about music is already in the music itself. You just have to listen carefully and train your ears to pick up the details.

For example, when I hear a piece of classical music, my ear automatically picks out individual instruments. I can hear what the clarinet or flute is doing. That’s how I learn.

Even now, I hardly ever watch educational content on YouTube, apart from maybe masterclass-style concert videos. For instance, I’ll watch someone like Cory Henry, an amazing pianist, play and explain what he is doing. But I don’t click on videos like “10 Things You Need to Know About This” or “5 Secrets to XYZ.” That approach just doesn’t work for me—it’s not how I learned to make music.

That said, everyone is different. If those kinds of videos help you improve, that’s great—you should absolutely use what works best for you.

Do you have a set process for starting to work on an idea from scratch?

My main instruments and entry points into a piece of music are usually the piano, drums, or percussion. These are my three main starting points. It could be as simple as practicing something on percussion, playing around on the piano, or recording a drum break. From there, I build out the piece step by step.

I almost never start with synth pads; I find them really uninspiring. Pads are just… space. I avoid anything that’s just “sounds nice” because it doesn’t give me the drive to keep going.

The way I make music, every step needs to inspire the next one. For instance, if I create a drum pattern, it needs to inspire the bassline, which then inspires the piano, and in turn, inspires the top-line melody. It becomes a chain reaction. Sometimes, it even circles back—after adding other elements, I’ll return to the drums to tweak something, and that change might inspire another idea.

I once read a book by English synth pioneer, Daphne Oram, who described the creative process in an interesting way. She said that the moment you first have an idea is like a peak—it’s when inspiration is at its highest. From there, it naturally starts to dip. The challenge is to keep reigniting that initial spark over and over so you stay inspired to work on the piece as long as it feels meaningful.

At the same time, there is also a point where you need to step away and avoid overworking it.

In your opinion, what makes a great hip-hop sample? And can you share a tip for new producers on how to improve their samples?

A good hip-hop sample starts with a great record. If you have a strong musical performance or a well-produced track, it naturally inspires the sampling process. Someone can take that record, chop out a piece, rearrange it, pitch it, stretch it, or process it in some way. But the foundation is always a good record—something sonically interesting and emotionally powerful.

A good record doesn’t have to be conventional. It could be very weird, feature an incredible vocal performance, or showcase great drums and bass. Anything compelling and unique can form the basis of a great hip-hop sample. The key from there is finding the right chop.

If you want to create great hip-hop samples, my biggest tip is to study records. This ties back to what I mentioned earlier—everything you need to know about music is already in the music itself. Listen carefully to a wide range of records—both old and new. Today, with platforms like YouTube and Spotify, you have access to an endless library of music. Immerse yourself in it, learn what makes those records stand out, and use that inspiration to create your own sound.

When I create samples, they’re often built from records I make myself.

I’d like to talk about one of the songs you co-produced, “7 Minute Drill” by J. Cole. We recently had Elyas on, and he shared his perspective on the track. Could you tell us your side of the story—how the song came to be? And what was your reaction when it was deleted after just one week?

I honestly can’t recall exactly when Elyas and I worked on the sample; it must have been over a year ago, maybe a year and a half. I had sent the sample to Conductor Williams, with whom I had just recently started working. I had been sending him material, but I didn’t even know he had used any of it.

The day before the album Might Delete Later dropped, Conductor messaged me on Instagram and said, “Yo, call me. We have a placement.” I called him, and he told me that we had a song with J. Cole. At first, I didn’t hear it. I asked, “Who?” And he said, “J. Cole. You know J. Cole, right?” I was like, “Oh, yeah, yeah, of course!”

He told me the song was dropping the next day. It was around 11 p.m. my time in Zurich, and the song dropped at 6 a.m. my time—just seven hours later.

The whole experience was surreal. The track debuted at number six on the Hot 100, which was insane. A week later, it was gone. That song now holds the record for the steepest drop-off from the Hot 100 because it was removed entirely. It was definitely strange, but I wasn’t frustrated about it. For me, it’s a good story.

What stood out most about the experience was realizing how quickly things can happen. I’m not the type of person who thinks, “This could happen overnight!” But when it actually did, I thought, “Wow, I guess it really can happen just like that.”

Which track that you’ve produced do you value the most or holds a special place in your heart?

The first one is “Parlez-Vous Anglais” by Headie One, featuring Aitch, and produced by Ambezza and me. That track is special because, when I made the sample, I genuinely thought no one would ever flip it. It was so complex—especially with the percussion—that I assumed it would be too busy to work with. But I still sent it out, and Ambezza did something incredible with it. His flip of that sample is just insane.

To this day, it’s the song I receive the most feedback on, even more than tracks with bigger numbers. Almost every week, someone reaches out about it—whether to ask how it came together or simply to tell me they love the song. Despite having fewer streams than my more popular songs, it remains truly unique, and I’m very proud of it.

The second would be the two tracks I did with Chance the Rapper, “Child of God” and “3333.” I love those songs for their musicality and message.

What’s your opinion on new technologies in the music industry, particularly the use of AI? Do you think it will change how music is made in the coming years?

I definitely think AI will change how music is made. Not everyone will use these tools. Personally, I don’t have an issue with new technology or AI itself. What I’m more skeptical about is the role of venture capital-backed tech firms in this space.

When a small, boutique company creates machine-learning music tools, I think it’s fantastic. I’m all for it. However, when large corporations step in, I think we need to take a closer look. It’s essential to understand how they train their data. This isn’t just about music; it applies to AI across all fields.

Tech companies have had it relatively easy for a long time. They tend to act first and deal with the consequences later, often by throwing money at problems. That’s where my concerns lie. For example, consider a company like Suno. They reportedly raised $125 million for a team of around 40 employees. Such funding is staggering.

That being said, I’ve seen some incredible things done with AI in music. About four years ago, Reske came to my studio and showed me amazing compositions created with machine learning—way before it became mainstream. Back then, it felt more like the “old-school internet” culture, with projects organized on Discord servers and small communities experimenting together. I loved that vibe because it reminded me of the internet in its early days.

However, as with anything that gets people excited, big companies inevitably step in and scale it up. That’s usually where I lose interest. If something starts to feel overhyped or over-commercialized, I tend to step back.

What advice would you give to young or up-and-coming producers on building their brand and expanding their work?

For hip-hop producers, being in a hub like Los Angeles is a huge advantage because that’s where so much of the industry operates. However, if you’re not in LA—or another major music city— you’ll need to find alternative ways to promote your work.

Personally, I chose to stay in Zurich, Switzerland, and I don’t plan on moving. This meant I had to figure out how to balance making music with getting it out there. This could mean promoting your music on social media, directly sending tracks to artists or collaborators, or even building something bigger around your work. For example, I started Minta Foundry, a sample pack brand.

The key is to put your work out there. If you’re not in a city where you can easily attend sessions and network in person, sharing your work is essential. You need to make sure people know about you.

Do you think posting “type beats” is still a valid way to promote yourself?

Honestly, I’ve never used platforms like YouTube or BeatStars to promote my beats or samples, so I can’t speak from direct experience. That being said, my advice is: don’t just copy what others are doing. Look at how they succeed, but find your own path and what works for you.

It’s important to do something that excites you because you’ll be doing it over and over again. Consistency is key, and if you’re not passionate about it, you’ll burn out. For me, putting stuff on the internet feels very personal. I like to do things my own way, and I’m not great at copying others.

I’ve been exploring other ways to release my music. For instance, I created a label called Minta Singles to release single records. I send these out as promotional copies to producers I know. I’ll hit them up, say, “I have these two songs on a record—do you want one?” They give me their address, and I send it over. I also sell them and share the tracks on social media.

What I like about this approach is that it’s something tangible. It’s not just a digital release that might fade with trends. Right now, I’m not sure if “type beats” will still be a thing in 20 years, but this physical record will always exist. It could show up in a record store, or someone might bring it to a flea market. It’s real—something that can survive trends. That’s why I’m focused on long-term value. Maybe I’ll even get a placement from it in 30 years—who knows?

What music do you usually listen to in your free time? Or are there some artists you especially enjoy now?

I mostly listen to two extremes: very calm music or very aggressive music. I don't really go for anything in between, like “nice” or feel-good music. For me, it’s either music that grounds me and helps me relax, or music that energizes and hypes me up.

For calming music, I really enjoy artists like Khruangbin and Hermanos Gutiérrez—they’re actually from Switzerland, but that’s just a coincidence. Their music really grounds me, and it has the same effect on my whole family. I can play it in the living room, and everyone’s nervous system just slows down. It’s incredible how music can shift your mood.

When I need to get hyped, I’ll put on something more aggressive, like Kendrick Lamar’s newer stuff or tracks by DJ Mustard. That gets me pumped. Overall, I don’t listen to anything in between these extremes, mainly because I already make that kind of music myself. So when I listen to music, it’s either to calm me down or to hype me up. That’s what I’m drawn to right now.

Where do you see yourself in, let’s say, five years?

I’ll probably still be right here. I don’t know, maybe in five years we can do the same interview again. I’m not sure, but I think I’ll be here because my studio is already the right size for me, and I don’t plan on expanding anytime soon. My goal is to keep making the music I make right now.

The challenge I keep figuring out is how to make money while still being able to create the music I love. The coolest thing about hip hop and rap is that it’s sample-based. And because it’s sample-based, any kind of music can fit into it.

When people ask me what kind of music I make, I say Rap, but that’s really only part of the story. It paints a picture that’s not quite accurate because I could be sitting here working on a classical piano piece, string arrangements, brass arrangements, recording double bass, vibraphone, glockenspiel, flute, or even some aggressive synth work. Since rap is sample-based, any genre of music can fit into it, and that’s what I love about it.

Follow Al Hug on Instagram: @_al_hug

More Blog Posts

See our latest blogs