Exclusive Interview

Nov 25, 2024

Produced by: Andrej Aroch

Edited by: Rudy Manager & Andrej Aroch

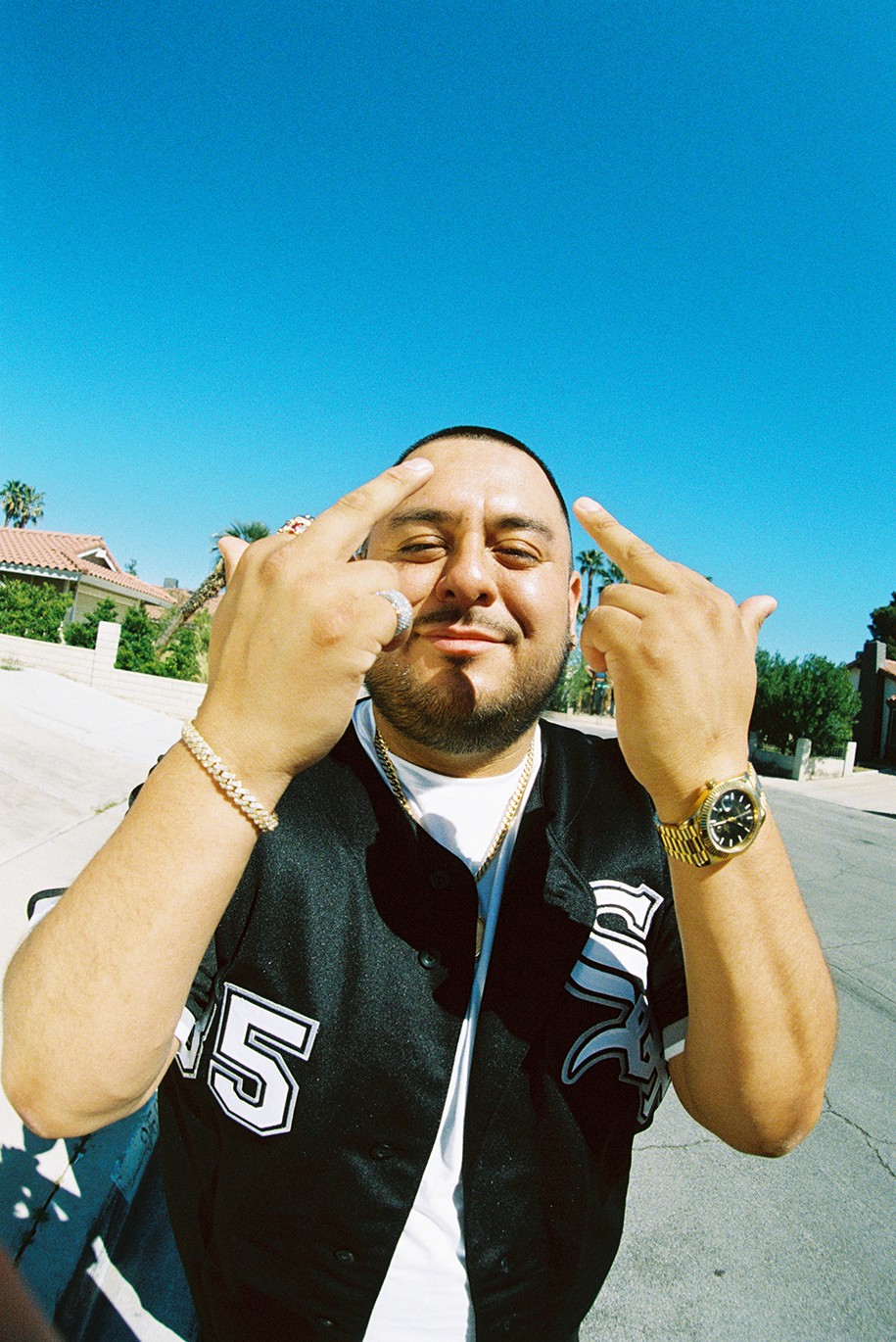

Fya Man – Father of Chicago Drill and Collaborator on Kanye West’s Donda

In this exclusive interview for Studio Talks, we sit down with Fya Man, often referred to as the “Father of Chicago Drill Sound.” Known for his innovative production techniques, Fya Man has played a crucial role in shaping the drill genre, collaborating extensively with Ye on his critically acclaimed album Donda. His impressive discography includes hit tracks with artists like NLE Choppa, Vic Mensa, Chance the Rapper, and Lil Durk, showcasing his ability to adapt and influence the ever-evolving landscape of hip-hop. Join us as we delve into his creative process, personal journey, and the future of drill music. The interview was conducted by Andrej Aroch via a video call on October 15th, 2024.

“Start where you are, use what you have, and do what you can”

- Fya Man

Could you share how you first got interested in music?

I first got into music when I was just a little kid. I’d watch people make music, especially in church. I remember seeing them do it at my granddaddy’s church. I used to watch The Temptations biopic over and over again. Honestly, my music journey started before I can even remember. My mom would tell me stories about how, as a baby, I’d always try to entertain people—singing or rapping in front of everyone. So, I’ve always loved it, and it’s just something I naturally gravitated toward.

What made you get into music production?

I needed beats, so I had to learn how to make them myself. That’s how I ended up getting into production—just so I could have beats to rap over. I wanted to rap, but when I tried explaining the sounds I had in my head to other people, they didn’t get it. So, I just started making the beats myself.

What was your process for improving back then? Did you have any mentors or were you mostly self-taught?

My mentors were my CD collection. I had this CD book with sleeves for the discs. When I was a kid, I’d go to Jewel-Osco, steal a bunch of candy, sell it at school, and then after school, I’d head to the corner store to buy bootleg CDs and build my collection. I was just listening to music all day, every day, whenever I was home.

That was my way of learning. I studied the greats, the people who made the music. We had programs on TV like 106 & Park—I watched that every day. From there, I just grew. At first, I’d emulate artists like Lil Wayne and T.I. That’s how I learned to write songs. I didn’t know anything about bars or structure, so I’d write a verse, and whenever T.I. stopped rapping, I’d stop too. I was tracing songs like that to figure out how to do it.

Can you share the backstory of how you connected with Kanye West and started working with him?

I had a single called “flee,” which came out in 2013 when I was in my group, The Guys. It blew up like crazy and is still a hood classic in Chicago. It’s kind of like the “Cha-Cha Slide” in terms of how much they play it at every party—birthdays, weddings, quinceañeras, bar mitzvahs, you name it. We really started taking over the city with that track, and it caught the attention of Malik Yusef, who’s also a mentor to Kanye. He became my mentor as well, taking me under his wing and teaching me how to go from being someone who makes beats to a true producer. He taught me about sound, texture, and a lot of other things.

In 2014, Malik brought me to LA for the Grammys. At first, I didn’t believe him—I thought he was just talking. We were at a meeting at Elevator, a platform in Chicago where I used to do my business meetings, and Malik was telling me all these big plans. So I kind of called him out and asked, "What are we doing next?" He said the Grammys were coming up in a month, and I didn’t take him seriously because I’d never even been to LA. My brother Smell and I went to LA for the Grammys, not to the ceremony itself but to all the events surrounding it—the gift suites and everything that happens beforehand. We got a chance to experience that and visualize ourselves being part of it one day.

It was during that trip that Malik introduced me to Kanye. When we met, Ye asked me what song had brought me there. So I played him “flee,” and he liked it. Then he asked me to play some other stuff, and I showed him a couple of tracks that were more reflective of my artistry, like “Chainz” and one another song from my EP at the time. He took a liking to my ideas, my style, and my pen game. That’s how I started hanging around them, kind of like the little homie, learning under their guidance.

In 2015, maybe a year later, I moved to LA. By 2016, I was working closely with them, but I hadn’t landed anything on any of the albums yet. I was just consistently working. Then in 2018, when Kanye’s Ye album came out, I finally landed my first track with him, “Wouldn't Leave.”

You have multiple production credits on the Donda album. How was it working on this album with Ye, and do you have any memorable stories from the sessions?

One of the most memorable moments from working on Donda was walking to the gas station with Jay Electronica to get blunts. That was crazy for me because he’s one of my favorite rappers of all time. I’ve always believed, and still do, that he’s one of the greatest to ever rap. For me, it’s him, Kendrick, Ye, and a few others who are just top-tier when it comes to their pen game. Jay Electronica writes songs that are impactful—he doesn’t care about making singles or hits. He just creates from the soul, and I really respect that.

It was interesting to just walk with him and see him as a regular person. It’s like seeing Superman without the costume—just hanging out with Clark Kent. That was a big moment for me.

Another thing that stood out was Kanye having Bible study every day at the stadium. I thought that was unique. We’d stop everything at a certain time each day and sit down for Bible study. It really created a synergy within the team. We also ate together every day, like a family. The magic of that album is hard to duplicate, and I think it’s because of moments like that—beyond just the music. We were all in sync, eating the same food, sharing the same space, and working as a unit.

I read that the Donda album was being finished in a stadium before the listening session. Were you there during that process, and how did the album change in those final days?

Yeah, I was there for the whole process. I was in San Francisco, then Vegas, Atlanta, LA, and finally Chicago before the album was released. In the stadium, right before it came out, there was a big change. We had the album finished, but then Kanye said, "Make the whole album into organs." Everyone was like, what? We had been working on the album all this time, and he really meant replacing everything with organs— just stripping it down to nothing but organs while still keeping the integrity of the songs.

So, we did that for the entire album. Some of the best tracks stayed as organ-heavy versions, and the organ became a key motif for the Donda album. Some songs didn’t work with the organ sound, but Kanye wanted to experiment and see how it would feel. That was the biggest lesson I learned—about post-production and how you keep working on a song even when it feels like it's done. It's not finished until it’s out.

Do you have a song or project you worked on that holds a special place in your heart?

Yeah, “Do It Again” by NLE Choppa and 2Rare. That one’s really special because it’s a story of perseverance. It’s one of the first samples I ever worked with when I learned how to sample back in high school, around 2005 or 2006. I kept revisiting that sample every year or two, trying to get it right and experimenting with different sounds as I improved. I’d try it over and over, and it finally turned into a hit song.

It taught me that if you have a sample or an idea you believe in, don’t give up on it. Keep revising it and trying it in different ways—maybe as a boom bap beat, then in a trap format, as a dance beat, or as a no-drum track, or even as a Detroit sound beat. Just keep experimenting. If you believe in it, stick with it. And eventually, it became 2Rare’s first hit, which is another reason why it’s special. As a producer, helping an artist reach milestones, like their first or second big success, is rewarding.

Working on Donda was also special for me because that was Kanye’s first time being nominated for Album of the Year, which was a huge moment. Being part of that legacy was incredible. Another highlight was the song I did for Lil Durk “I Get Paid,” which was his first time getting attention from major media outlets like The Fader and Complex. Moments like those are unforgettable.

Even with SahBabii, who made “Pull Up wit ah Stick,” his first-ever video was for a song I produced called “Nailin N***as.” Giving someone that spark, that first big push, and seeing them take it further—it’s all about helping outline their career, and I love being a part of that.

How do you think drill as a genre will evolve or develop in the upcoming years in the music industry?

I believe drill is here to stay. It’s not going anywhere. Just like when Ice-T and N.W.A. emerged with reality rap, painting the pictures of life in the hood, drill will continue to evolve. We might not call it “the hood” anymore; we refer to it as “the trenches,” but the stories told and how people communicate in those spaces will always resonate.

The lingo will change, and the way people express themselves will evolve, but drill music will stay forever. It will always represent an alternative voice in the music landscape. There will always be various types of music, but the trenches will have their own distinct voice, just like they always have.

Some of the negative aspects associated with drill will continue to change, as will the positive elements. Personally, I try to contribute to the sound while steering away from producing diss tracks. I won’t speak on the ones I originally produced that helped propel the sub-genre, but I’ve realized they left a bad taste in my mouth because of their negative impact.

I still love the genre and its potential, but I prefer not to participate in the diss aspects of it anymore.

What advice would you give to new or up-and-coming producers trying to establish themselves and start working with artists?

Build from the ground up with people. Avoid chasing clout. D**k riding is not a form of transportation. It’s not a legitimate path to success. Instead, focus on being genuinely valuable to others and helping them in meaningful ways.

Try not to shoot for the stars in terms of artists; instead, shoot for those you think can be the next big thing. Aim to discover talent rather than only targeting established artists. Be your own A&R and look for individuals you believe have the potential to succeed. Research their qualities—consider their unique voice, the stories they tell, or any special characteristics you can sense. If you see something unique in someone, work with them, regardless of whether they can afford it. Think of it as an investment in yourself and them.

Keep sending out beats and stay diligent. Use Instagram to build authentic connections; instead of just asking if you can send beats, engage them with thoughtful questions unrelated to music. Establish real conversations and let relationships develop organically.

For those who are more socially inclined, attend open mics or events like Music Mondays in Atlanta. Engage with people where music is happening. You might discover someone who isn't getting much attention but has potential. However, don't believe in someone more than they believe in themselves. That will drain you emotionally. If you're constantly trying to convince someone to pursue their passion, it’s a red flag.

People who truly have the drive will pursue their passion relentlessly. If you feel you need to convince someone to take action, reconsider your belief in them. Don’t just believe in their talent; believe in their work ethic. Their work ethic and willingness to put in effort are crucial indicators of their potential.

Also, be cautious of individuals who have been abandoned by others in the industry. While it may appeal to your ego to want to help them, ask yourself why others have left. If no one supports them, it might mean they haven't contributed positively to those relationships.

On the other hand, it's encouraging to see someone with a support system, even if it's just a friend or family member. If you find someone working hard on their own, it shows determination, which is a good sign.

Start where you are, use what you have, and do what you can. Let everything else fall into place.

Do you have any upcoming projects or plans for the rest of the year or in the upcoming months that you're excited to share?

I’m really excited about several projects coming up! FendiDa Rappa is dropping new music, and I’m looking forward to new releases from SkinBone and Bella Blaq as well. On my end, I have personal music and clothing projects coming out, and I’m currently working on my first feature film as a writer and director.

I also have a couple of acting roles lined up. One of them is called If It Bleeds, directed by Matthew Hirsch, and I’m thrilled to be part of that. Plus, I’m looking forward to the new season of P-Valley, where my wife Bella Blaq is co-starring. I’m excited about Malik Yusef’s new album.

I’m really excited for what God has in store for my family because it’s not all glitter and gold. I’ve been dealing with some personal challenges, particularly being estranged from my son and daughter in Florida. Not being able to speak to them has been really painful. I’ve always been somewhat closed off, but I want to open up more about the real struggles in my life.

I’m praying for healing in those relationships. It’s tough because when you move on, some people may use your love against you. You have to be cautious about who you surround yourself with, as you might end up fighting battles to keep your family together how you want to.

I carry a lot of knowledge, wisdom, experiences, and memories that I’ll always share with my children, but I feel like I’ve been robbed of that opportunity. It weighs heavily on my heart, but I’m determined to keep making music, empowering others, and giving hits to artists like NLE Choppa, even when I’m going through my own battles.

The key is to keep going despite the challenges. Everyone faces their own struggles and traumas. Sometimes, your gifts can be the very tools you need to overcome your obstacles.

There’s a parable my grandfather used to tell about a man stranded in the ocean who prayed to God for help. When two boats came to rescue him, he refused their help, saying, “God has got me.” Ultimately, he drowned and asked God why he wasn’t saved. God replied, “I sent you two boats!”

So my advice is to stay resilient and trust the Most High. Trust Allah. That's what it’s all about.

Follow Fya Man on Instagram: @fyamanhof

More Blog Posts

See our latest blogs