Exclusive Interview

Mar 21, 2025

Produced by: Tadeáš Jánoš

Edited by: Rudy Manager & Andrej Aroch

Juke Wong – Inside the Japan Documentary & Made to Inspire Series

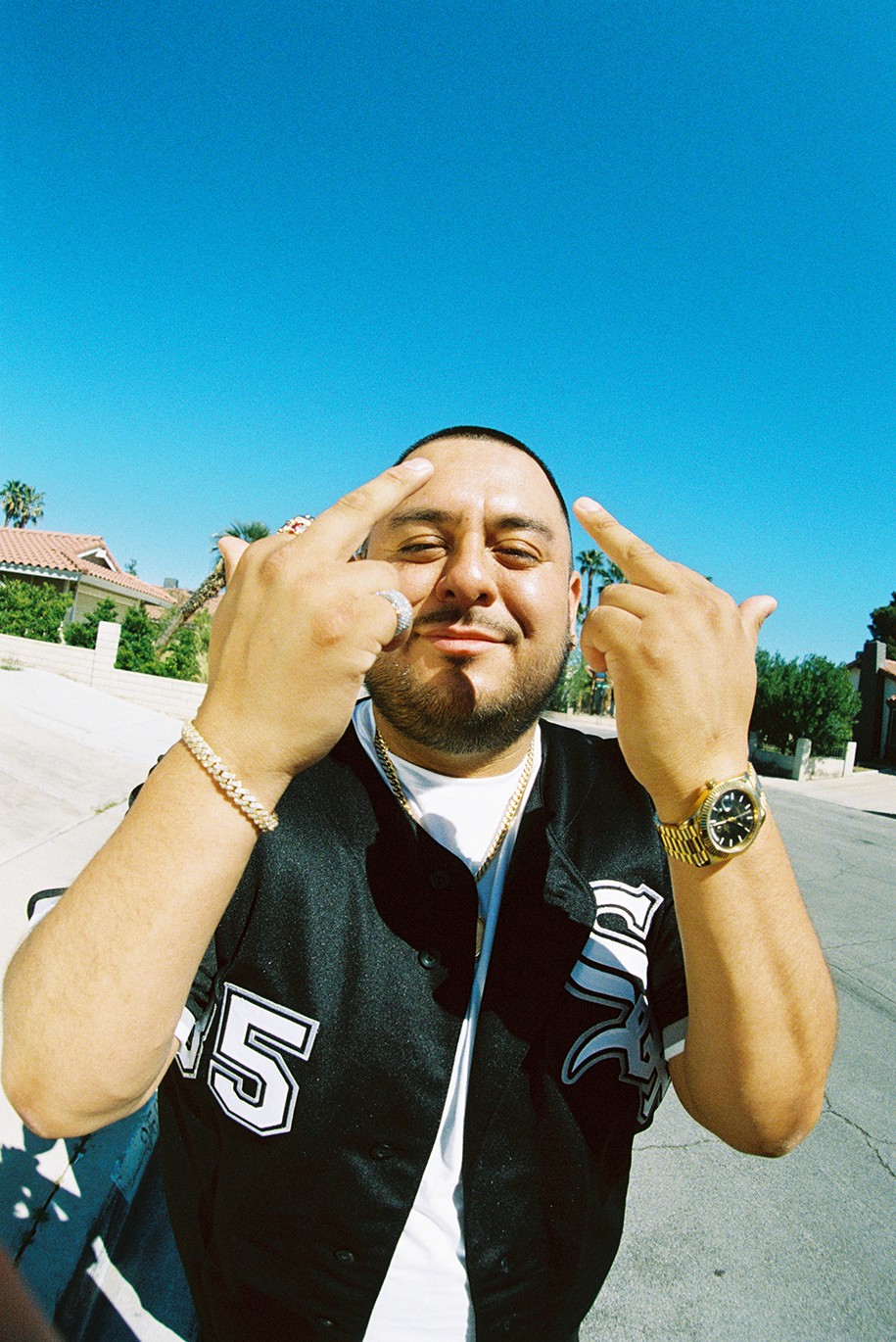

Welcome back to another Studio Talks exclusive interview. Today, we have a special returning guest, Juke Wong. If you’ve been following his journey, you already know he’s a powerhouse producer with an insane work ethic. This time, he’s back with something even bigger—a full documentary capturing his creative process in Japan. We’re diving into everything from making beats overseas to how he created the Made to Inspire series and what he learned along the way. This interview was conducted on March 8th, 2025.

“I’m doing this to make a positive impact and inspire others through my music”

- Juke Wong

When did the idea of a documentary first come to you?

Kind of like last summer. I was just doing the same old—working in Chicago every day. That’s when I booked my flight to Japan. And I was kind of unsure about it because I didn’t know all these records were coming. I just wanted to make music out there. But then I thought it’d be cool to make a cook-up vlog.

And, there’s a documentary series by IN THE LAB and Devin Williams called 10000 Hours. I watched it a lot as a kid, and even to this day, I still watch it just to get motivation. It’s about basketball. That summer, I thought—it’d be cool to have a music producer version of that.

Why did you choose Japan?

I mean, obviously because I watch anime and stuff—that’s one reason. But also when you think about Japan, you think about advanced technology, futuristic infrastructure—just a more futuristic society. And it’s unlike anywhere else in the world.

People be doing cook-up vlogs in LA, Atlanta, and New York, and my whole thing is, I always want to be unique in everything I do. So I felt like Japan was the perfect place because nobody had done it before—going there and making a whole cook-up vlog for a month. So I think that’s why I chose it.

Did you prepare for the trip in any specific way?

No, not really. I was just living life—I didn’t even pack my bags until like six hours before the flight. I was just doing my thing—still cooking up, still working.

How did you arrange all those studio sessions in Tokyo?

I had reached out to a couple studios when I booked my flight, just to see if I could rent them out for a whole month. And then this one guy in Tokyo pointed me to a website called Studio Noah. It’s kind of like— I don’t know if you guys know about Pirate Studios in London—but it’s basically the Tokyo version of that.

And funny enough, when I landed, I got to my Airbnb and tried to book a studio, but I had to sign up for the website. And I couldn’t sign up unless I put my name in Japanese. I had no idea how to do that. But I had one follower from Japan—he was actually in the documentary; you saw him in the studio with me. I just asked him, “Hey, can you type my name in Japanese real quick?” And he did that as soon as I landed. After that, I signed up for the studio website, booked my sessions, and from there, I basically just booked a session every day.

In the documentary, you spend a lot of time working alone in the studio. Is that your usual process, even back in Chicago? Or do you prefer collaborating with other producers and enjoying a more crowded vibe in the studio?

Depends, man. I got a lot of homies in Chicago I cook up with—even in LA and London, I always collab with people. But when I’m in Chicago, my studio is only about 10 minutes from my house. So I find myself here most of the time.

My studio is out of the way, so it’s a hassle for people to get here—which I don’t mind because I like working alone anyway. So I’d say it’s a mix of both, but when I’m in Chicago, I mainly work alone.

Back to Japan—did you get a chance to explore the local music scene?

I did. When I was out there, I looked up a bunch of Japanese jazz and orchestral composers, and I would just be listening to them while walking around Tokyo.

I actually got the chance to go to Sony Music Japan since I’m signed to Sony. I linked up with a few people and had some sessions toward the end of the trip that I filmed, but I didn’t feel like they fit in the documentary. But I got to meet some Japanese artists, some Japanese songwriters, and go to the Sony studio.

The Sony studio was crazy—one of the wildest studios I’ve ever seen.

You often get into the studio at 9 or 10 p.m. and leave at 5 a.m., putting in hours of work. What’s your work rate like when you’re making music? And do you think everyone should treat production like a full-time job?

I would say if you want to be good at it, yeah. I definitely believe that the more time you put into something, the more benefits you’ll get out of it. That’s the approach I take.

It’s the same thing as when I was a kid trying to make it to the NBA—I spent a lot of time just playing basketball. Every New Year’s Eve, I had a tradition from December 31st into January 1st. I used to be in the gym at midnight, getting shots up as the clock hit the new year. I didn’t really care about going to any New Year’s parties.

Now that I don’t play basketball anymore—I still hoop on the side, but music is my job—I’m always in the studio when the New Year hits. Just keeping that work going from the old year into the new one.

It was a pretty long trip, around six weeks, right?

Yeah, it was supposed to be four, but I was like, “Man, I gotta stay an extra two weeks.”

What did those six weeks teach you, both as a person and as a music producer?

Man, I learned that you choose what you want to do every day. Going to the studio every day, I faced burnout at times and wasn’t always inspired. But I was still in Tokyo, and I knew my time was limited. So no matter what, I booked the studio every day.

The biggest thing I learned is that everything connects—how your day goes affects everything else. My routine was to wake up, eat, shower, and do all that. Then I’d go to this one building in Shibuya—it’s called Shibuya Hikarie. They have a public lounge on the 11th floor, so you’re looking over the famous Shibuya crossing. My sessions would start at 11, so I’d probably get there around 9 or 10 and cook up for a couple of hours before heading to the studio.

I really just learned that the mind is a powerful tool. Whatever you set your mind to, you can do. Some nights, I cooked for eight to ten hours straight with no breaks—it got tough. But I also realized that at the start of a session, I might not be making my best stuff—but by the end, after making three or four beats, that’s when I’d make my hardest s**t. So I feel like you have to push through obstacles to get where you want to be.

You handled everything for the documentary—from production and editing to filming, directing, and publishing. What part of that was the most challenging?

I would say editing. When I came back, I didn’t start working on the documentary until January. I thought, “Man, I don’t know how to edit anything.”

I mean, I had edited my YouTube loop breakdown videos before, but this was a whole different level of intricacy and detail. It took a lot of trial and error. Whenever I thought I had the final version, I’d show it to my friends, and they’d give me constructive feedback—like, “I think you should do this or that.” And obviously, I listened. That’s why it came out the way it did.

It was a tedious process. I really slowed down on music—not completely, because I always have the itch to cook up—but editing took up so much time. Man, I put crazy hours into it—eight to ten-hour sessions in the studio, just editing instead of making music.

At the same time, it was the most fun part. It felt like I was really making a movie, and I got to see my vision come to life. So all the time I put in was definitely worth it.

You cooked up a lot of beats during your time in Japan. What placements did you get from those beats? We know about “Stuff,” right?

I also did “Stiff Gang” in Japan. In fact, I made the loop there.

I could have had footage of me making “Stiff Gang” in the studio, but as I was working on the loop, I thought, “I don’t even like this anymore.” So I deleted the footage.

I spent two hours making the loop and the beat, but I wasn’t feeling it at the time. So I deleted it. Two months later, it became one of my top three favorite placements ever.

It’s like “pushin P”—the ones you least expect always land.

The culture in Japan is quite different from the U.S. Was there anything that really surprised you during your time there?

I would say the fact that they don’t have public trash cans. If you have plastic wrappers, bottles, or cans, you usually have to wait until you reach a convenience store to throw them away. Since I was always moving around, I carried a plastic bag for my trash until I got back to the Airbnb.

I also noticed how reserved everyone was. I wouldn’t say they kept to themselves completely—people still helped me when I needed it. In public, no one approached me or told me I was doing something wrong. Obviously, I wasn’t—I was in a foreign country and wasn’t trying to get arrested.

At one point, I didn’t talk to anyone for a week, except for the convenience store staff near my Airbnb when I got food. Just seeing how everyone was kind of in their own world was definitely interesting.

How did that inspire you? Was it the landscape, the jazz we talked about, or something else that sparked your creativity?

It was just me, totally zoned in. Since I didn’t know the language, I couldn’t really talk to anyone. It was just me and my own thoughts most of the time.

There was one place called Enoshima that I went to while I was in Tokyo, and just going there brought so much inspiration. The scenery was amazing, and I knew it would translate into my music.

I’d also say the food played a big part. Eating healthier food every day, compared to what’s typically fed in America, definitely helped.

You mentioned that this is part of your Made to Inspire series—four documentaries you plan to make. Do you already know what’s coming next?

I actually want to make five parts.

For the second one, I’m planning to film it from May to August this year and release it around November. I think this one will be set in Chicago—or possibly around the U.S., since I might be traveling soon. It’ll probably be a mix of different places I visit, but mostly Chicago.

I have some cool ideas that will feel fresh compared to this one.

What countries would you like to visit?

One place I really want to visit someday is Moscow, but I’ll wait until it’s safe.

I’m also thinking about doing one in Korea and London—since London feels like my second home. I’ve spent so much time there that I feel like I have to do one.

Aside from that, nothing else really comes to mind.

Fans Q&A

Current favorite VST for synths and effects?

That’s tough. I recently got Notonic 2 and Scorch, and those have been pretty dope.

For synths, Analog Lab is cool. And of course, The Prince—I made “Dum, Dumb, and Dumber” with it.

As for effects, I don’t use them much in my music. I probably should, though, since I have a bunch of effect plugins on my laptop that I haven’t used yet.

I don’t really have any go-to effects plugins. Omnisphere 2 is great for synths too, but I feel like everyone has it now.

Lately, it’s just been Notonic 2, Scorch, and The Prince—that’s it.

What do you think younger producer loopmakers do that ruins connections?

I get it—I was like that too. When you’re hungry and eager, it’s easy to chase every opportunity. But there’s real value in building one solid connection, rather than having 10,000 surface-level ones. Find someone you connect with and build something meaningful.

Another thing—so many producers and loopmakers follow trends. I get it, I’ve done that too. But honestly, everyone needs to develop their own sound and bring something new, instead of copying what’s already popular. That’s how music gets stagnant—when everyone makes the same thing.

So focus on being unique and building meaningful connections. You don’t need thousands—just one good connection can change everything.

Can a producer’s life change from one moment to another?

For sure. I was working at The Home Depot when “pushing P” dropped.

Even after it came out, I worked there for a month. Every day, I’d go to The Home Depot, playing “pushing P” on the way there, back, and when I woke up—just nonstop.

To everyone else, I was just a regular dude. Nobody knew I had the hottest song out at the time.

Yeah, life can change in a moment. I feel like when you put in enough time and stop worrying about what you’ll get out of it—when you do it for love—that’s when the universe rewards you.

How much do you get paid per placement?

Uh, it depends. For my first song, I got $1,500 for the advance. But the highest one recently was around $10,000.

Have you ever had moments where you said to yourself, maybe this isn't for me?

All the time. I still have those moments now. There are still times I doubt myself or feel like I’m not at my best. But every time, the universe shows me I’m on the right path. It’ll hit me with something big, like four records on Future’s project.

I felt that way in Japan as well. By the fourth or fifth week, I thought, What am I even doing with my life? I had spent so much money on studio time. Not that it’s a bad thing—it’s an investment in myself—but I still felt burnt out, uninspired, and exhausted from working so hard.

Even now, I still have those moments, but I remind myself—why am I doing this? Am I doing it for money, clout, or fame? No. I’m doing this to make a positive impact and inspire others through my music. That’s why I keep going. It’s a purpose greater than myself—giving back to the world, if that makes sense.

Follow Juke Wong on Instagram: @jukewong

More Blog Posts

See our latest blogs